When a Peace Corps Volunteer finishes his or her service, it’s referred to as COS (Close of Service). And it’s very common for Volunteers to celebrate their accomplishments and embrace their new freedom by taking a COS trip. Usually it’s an adventure to transition between life abroad and a new life in America.

When I COS’ed at the end of September, I knew I had another adventure waiting for me in India. I had planned a month of traveling in the world’s second most populated country as a way to mark the end of three years in Madagascar and to help me begin the transition from rural Malagasy life to bustling and modern American life. As I began traveling in India, I noticed many things that reminded me of life in Madagascar. I also realized that if it hadn’t been for my previous experiences in Madagascar, I would have most likely reacted to these new Indian experiences differently and possibly developed a more negative outlook of the country because I would have been more uncomfortable in these new settings.

Like many things in life, we normalize ides as they become routine. As they become more routine and common, we tend to be unfazed by their relative difference or shock, as perceived by others who are less familiar. When I kept having moments in India where I thought, “hey, this reminds me a lot of Madagascar,” I knew something was changing inside of me. When I could step out of my mind and realize that what I was feeling about Madagascar was happening right before my eyes in India, I felt compelled to start a running list and share it with my readers.

In no particular order or significance, these are the seven ways that I believe Madagascar prepared me to be a better traveler in India:

1. Trash and road conditions

In India, there’s a lot of trash. I won’t get into the why or how of it, but trust me—there’s trash seemingly everywhere. It can smell, it can look unpleasant, it can be overwhelming. But I had been living in similar circumstances in Madagascar, so it wasn’t as much of a shock to me in India. Without a lot of public infrastructure to deal with trash in either country, it piles up along the streets and in open fields or plots of land.

Other aspects of India’s infrastructure, specifically roads, seemed downright pristine in my eyes. Coming from a country where if you’re lucky enough to have a paved road it probably has a bunch of potholes, to a country where almost every street is paved AND has lanes painted was a real treat for me. I was visibly smiling for the first few days whenever I got into a car, while on the other hand, my friends and other travelers looked more nervous or put off by their perceived low quality of Indian roads.

2. Challenging creature comforts

More than once in India, I had a thought that was along the lines of “this toilet is disgusting, but at least it’s not as bad as a kabone (pit latrine)!” In many of the Indian toilets I used, there are even these cool butt hoses to use instead of toilet paper. Whether it was an air conditioning unit that was out of order, a television that only had 2 channels, or a sub-par Wi-Fi connection, I was coming from a place where those things were considered luxury items and I could deal without them. Some of my fellow travelers felt a little more…entitled…to these things than I was.

3. Long drives and travel times

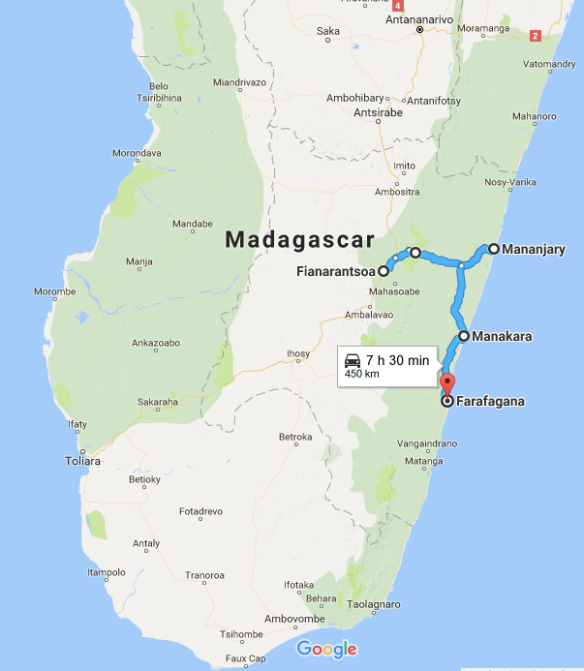

Getting around India is relatively easy, efficient, and affordable, in my eyes. There are lots of car or bus options, as well as a connected rail system. So when I would meet other travelers who complained about 4+ hours traveling on a bus in India, I had very little sympathy. In Madagascar, what you are told will be an easy 3 hour taxi-brousse ride often turns into a 7+ hour ordeal on an old minivan held together with duct tape where you’re crammed in between two sweaty Malagasy people, chickens nipping at your ankles from under the seat, and music blasting in your face as you fly down a windy road riddled with potholes and stray cows. Sounds charming, right? On the flip side, in India, a comparable journey takes place in a well maintained commercial bus with assigned seating, air conditioning, and a reliable travel time because the roads are predictable. While I met some travelers who dreaded the idea of a 4 hour train ride in India, I was excited because it would probably comfortably cover more distance in less time than other options in Madagascar.

4. Language barriers

Almost every Indian person that I met spoke at least basic English and many people were advanced speakers. Coming from a country where few people outside of my students or work colleagues spoke any English, I was overjoyed that I could speak so freely with almost anyone in India. The tricky part was adapting to the Indian accents and vocabulary. I frequently found myself searching for linguistic common ground, something I was very used to doing in Madagascar. Rephrasing questions, using simple vocabulary, or just surrendering to the idea that I would remain partially clueless during a conversation—these were skills that I learned in Madagascar and easily transferred to India. Non-verbal communication in India was another idea I had to adapt to, where something as simple as the direction or force of your head nod can speak volumes above the actual words you utter.

5. Trust

At many times during my travels in India, locals and other travelers would give me unsolicited advice about maintaining my personal safety and health. When my initial reaction to these ideas was “Duh, of course that makes sense,” I knew that I had a skill set from Madagascar that I was starting to take for granted: street smarts in the developing world. Whether it was dealing with pushy taxi drivers, street vendors, children begging for money, or being in crowded unfamiliar places, I trusted myself and those around me like I did in Madagascar. It wasn’t entirely new for someone to try to take advantage of me because I am a foreigner, so I tried to keep that in the back of my mind. Dealing with similar situations in Madagascar helped me recognize, and mitigate, them in India.

6. Being a good passenger

In both Madagascar and India, people drive very differently than they do in America. I would describe their approach to driving as doing whatever the driver wants while making sure there is a small buffer of safety around the car. In America, driving lanes, posted speed limits, and rules of the road are all generally accepted and obeyed by drivers. In Madagascar and India, these things feel like mere suggestions. It was not uncommon for me to be a passenger in a Malagasy car when the driver would try to pass a slower car on a two-lane highway while coming within a few feet of oncoming traffic before darting back into the original lane. After a few instances of this, I learned to calm down, trust the driver, and basically surrender to the idea that either everything would be fine or I’d be involved in a massively horrific vehicle accident. This also meant I was already prepared for the same behavior from drivers in India. While other passengers winced or gasped as we crossed into oncoming traffic or came within inches of hitting a stray cow in the street, I tended to remain present in conversations or gazing out the window like nothing was happening.

7. Cash based economy

In Madagascar, cash is by far and away the primary monetary tool. I can probably count on one hand the number of times I saw a credit card machine in the three years I lived there. In India, cards are slightly more prevalent but cash is still the best way to get around. I was used to being conscious of how many small denomination bills I had in Madagascar, because breaking large bills in the countryside was nearly impossible. Those same instincts kicked in while I was in India, so I was very comfortable living day to day with cash.

A few extra things that surprised me about India

- In the south (Kerala, from my experience), there are more churches and cathedrals than I expected. Many of them were ornately decorated and flashy.

- Billboard advertising is extremely common—everything from political coalitions to the newest smartphone with an impressive selfie camera.

- Most Indian men have a full thick head of gorgeous hair. I definitely experienced some hair envy.

- Women dressed in beautifully designed and colored saree as everyday clothing. Much like the Malagasy lambahoany, I never saw the same saree design twice.

- Unexpected warmth, hospitality, curiosity, and helpfulness of local people. I could go on for days discussing this, as it also reminded me of the nature of most Malagasy people.

- More than just stray cats and dogs—cows, goats, monkeys, and donkeys are commonly wandering the streets of India like they own the place.

- Vehicle traffic, congestion, car horns, and aggressiveness really got to me after a while, eventually becoming a full on auditory assault.

- Air pollution is much worse than I anticipated. On some evenings, the sun set behind a layer of pollution before it reached the actual horizon.

- A fine appreciation of electrical outlets—availability in cafes and restaurants, placement near beds, and a convenient switch to turn the outlet on or off. This made traveling and charging devices so easy!

Overall, I absolutely loved traveling in India and I would go back in a heartbeat. The people, the food, the history, the natural beauty, and the spiritual magnetism were all so accessible and kept me in a constant state of awe. I don’t think I would’ve had the same positive experience if I didn’t get help organizing my trip from the great team at India Someday. I can’t recommend them enough and they made my first trip to India feel less intimidating and smooth. Please check out their website for more info, especially if you’re planning a trip to India in the future. And you should go, right after you visit Madagascar!